Government Tax Credits To Drive Electric Vehicle Adoption

The U.S. government is taking big steps to electrify the transportation sector. There were an estimated 630,000 electric vehicles (EVs) sold in the United States last year—4.6 percent of all car sales. EV sales grew 114 percent from 2020, when only 294,000 EVs were sold.

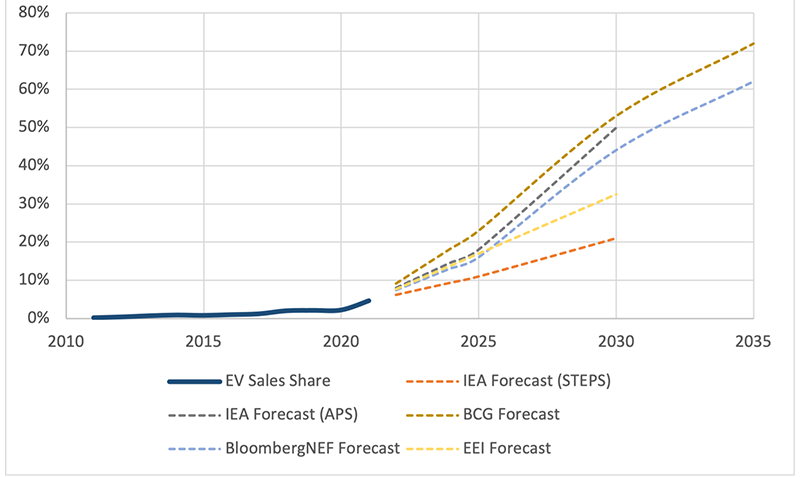

With the help of U.S. federal policy boosting demand for EVs, and car manufacturers pledging to speed up production and roll outs of new EV models, their share in U.S. car sales is expected to grow through 2035.

“However, it’s unclear whether all of this will be enough to help the United States reach its very ambitious EV goals of 50 percent share of all new-car sales to be EVs by 2030, or if additional help will be needed,” CFC Analyst Chris Whittle said. “It’ll be a tall order to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.”

The bipartisan infrastructure bill signed by President Joe Biden in November set aside investment funds for EV-charging infrastructure in the hopes of developing a 500,000 EV charger network. By the end of August 2022, the United States had 50,456 publicly available EV charging stations with 126,320 EV supply equipment ports. Numbers for charging stations and EVSE ports grew significantly during the first eight months of 2022.

Range anxiety remains a big issue to potential EV buyers. “Seeing the growth in the U.S. charging network will relieve some of the concerns over range anxiety and should continue to push demand of EVs,” Whittle said.

The Inflation Reduction Act contains consumer demand incentives for purchasing EVs. Specifically, buyers could receive up to $7,500 in tax credits for new EVs and $4,000 for used EVs.

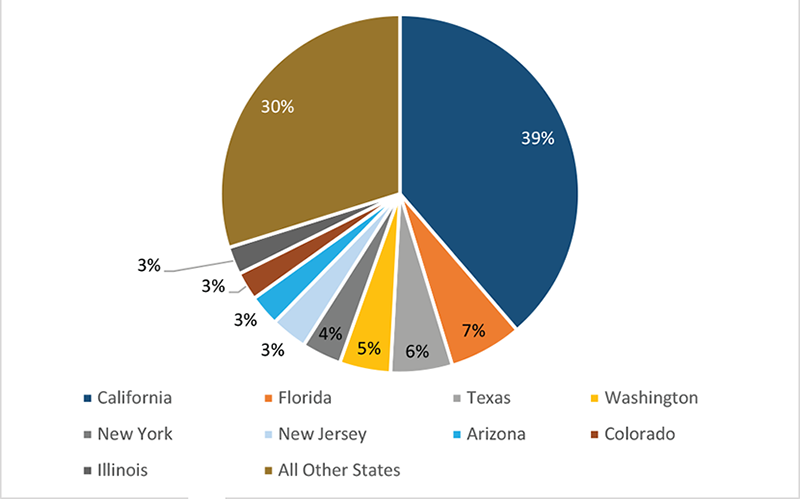

Percent of Registered EVs by State

“These credits do a good job of lowering the total cost of ownership for EVs, which should help to increase the demand for EVs,” Whittle explained.

State governments also have been looking for ways to boost demand. This summer, Nevada and Minnesota joined California and 10 other states in agreeing to establish zero-emission vehicle quotas for new passenger cars.

The political focus on incentivizing consumers will significantly grow the EV share of new-car sales. BloombergNEF forecasts EV sales will make up 16 percent of all new-car sales in the United States by 2025, 44 percent by 2030 and 62 percent by 2035. It projects the United States will miss its 2030 EV sales goal. BloombergNEF’s pessimistic outlook is likely in response to the lack of a strong domestic EV supply chain.

U.S. Car-Sales Share - EV (%)

Pressure on the supply of critical materials will be an obstacle as the United States tries to reach its EV goals. Additional investment will be required in the near term, specifically in mining, where lead times are longer compared with other parts of the EV supply chain.

More than half the global lithium, cobalt and graphite processing and refining capacity is in China. The country also produces three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries and is home to 70 percent of production capacity for cathodes and 85 percent of production capacity for anodes. Both are key components of EV batteries, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Experts believe the majority of EV battery production is likely to remain in China through 2030, with 70 percent of battery production capacity already planned. These numbers contrast with that of the United States, which has only 10 percent of global EV production and 7 percent of global battery production capacity, according to the IEA.

There is a possibility that all these EV policy incentives on the demand side could push for a growth in mining and battery production in the United States or in U.S.-allied countries. If demand increases fast enough and domestic supply chain infrastructure is not in place, it could push the United States to continue to import Chinese materials and batteries despite the high import tariffs. This could continue to slow down EV adoption with longer lead times and higher prices. The reliance on China could also make EV deployment highly vulnerable to geopolitical risks—all of which could make it very hard for the United States to reach its EV sales goals.

“With all the uncertainty surrounding the future supply chain of the electric automotive industry, it’s hard to say exactly where we will be in the next 10 to 15 years,” Whittle concluded. “Regardless, electric cooperatives should prepare for more EV ownership and higher charging demand in their service areas for the coming years.