Eyes on the Economy: Employment Report, Construction Spending

Economists Miss Big on Employment Report

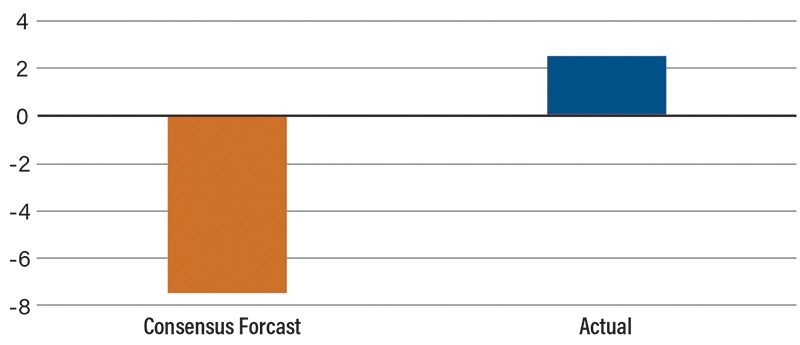

The economics profession sometimes struggles with forecasting, and the May employment report is a good example of just how wrong they can be. Granted, the forecasting horizon is foggy, but it was the biggest miss since the last recession ended in 2009.

Economists had predicted the unemployment rate would peak at 20 percent and nonfarm payrolls would decline by another 7.45 million jobs this year. With 43 million jobless claims filed over the last 11 weeks and the labor market seemingly in a death spiral, it’s easy to see why such a doomsday outlook materialized.

However, in an about face, the May unemployment rate fell to 13.3 percent and the economy added 2.51 million jobs. The good news saw the stock market shoot up and the yield on the 10-year Treasury jump 25 basis points. So, why the miss? One theory gives credit to government efforts, especially the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which provided relief to small businesses through forgivable loans used to rehire and pay employees. Restaurants and retail stores were top beneficiaries of the PPP.

To add even more mystery to the turnaround, reporters are pointing to a footnote on the May report indicating there are calculation errors in the report, and the unemployment rate probably should be 16.3 percent for May and 19.7 percent for April. The Bureau of Labor Statistics does its upmost to maintain data integrity, but there are extraordinary challenges in collecting real-time data during a pandemic. For example, a lot of people stopped looking for work while the pandemic raged or had their hours reduced. These people are not counted as part of the official unemployment rate.

Economists predict employment will improve through the third quarter. Estimates call for the U.S. labor market to regain about half the lost jobs by year-end. Of course, this is highly dependent on the country not staring down the barrel of a second wave of infections. Expect the unemployment rate to end the year around 10 percent.

A full recovery won’t occur in earnest until a vaccine is widely available by the second half of 2021. Don’t expect the U.S. to return to pre-COVID-19 employment levels until the end of 2023.

May Nonfarm Payroll Report

(Numbers in Millions)

Construction Spending Falls, But Beats Negative Forecast

Total construction spending decreased 2.9 percent from March to April, registering well above the consensus estimate of a 5.3 percent decline, thanks to stronger-than-expected spending in nonresidential construction. April’s decline was driven by a 4.5 percent contraction in residential outlays.

Plunging spending for new residential construction has been softened by increased activity on residential improvements. Economists project the housing sector will recover in the second half of the year, but further declines are expected before that happens.

The nonresidential outlook is grim, especially the hotel segment, which is experiencing a drastic decline in occupancy and revenue due to a practical halt in personal and business travel.

All referenced economic data sourced from Bloomberg.

Recent Economic Releases

| Indicator | Prior period | Current period (forecast) | Current period (actual) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction Spending (Apr.) (MoM) | 0.9% | -5.3% | -2.9% |

| Nonfarm Payrolls (May) | -20.5 M | -7.45 M | 2.51 M |

| Unemployment Rate (May) | 14.7% | 20.0% | 13.3% |