The Market, Not the Mandate: What’s Driving Interest Rates

In early 2026, much of the public conversation around interest rates remains tightly focused on the Federal Reserve—who will lead it, how fast it may cut rates and how low policy rates might go. While monetary policy certainly matters, this focus risks overlooking several forces that are likely to shape interest rates more decisively over the coming year. A broader view suggests that even in an easing cycle, interest rates—particularly long-term rates—may remain structurally elevated.

Monetary policy matters, but its reach is often overstated. The Federal Reserve controls the federal funds rate, an overnight lending rate that primarily influences short-term borrowing costs. Changes in this rate affect financial conditions mainly through expectations, not through direct control over most consumer or business lending rates. Those rates are typically benchmarked to Treasury yields, which are determined by market forces.

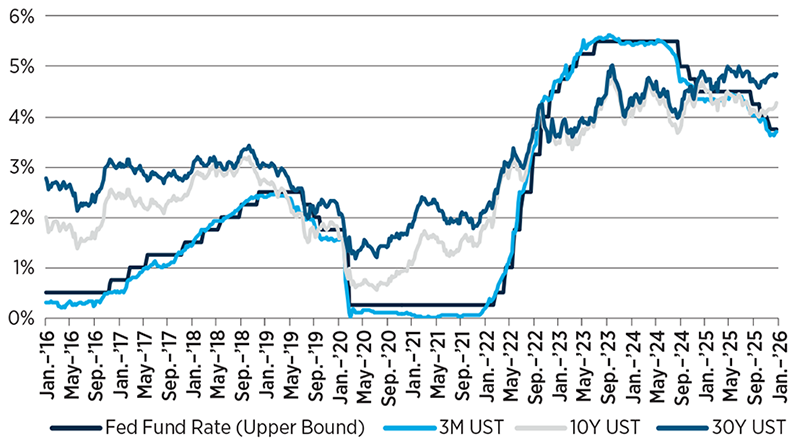

Short-term Treasury yields compete directly with the fed funds rate and therefore respond closely to policy changes. Long-term Treasury yields, however, operate under a different set of dynamics. While they may move in the same general direction as policy rates at times, the relationship is neither tight nor consistent.

Recent history illustrates this clearly. During the 2022–2023 tightening cycle, the fed funds target rate peaked at 5.5%. Yet the 10-year Treasury yield never consistently reached that level, and the 30-year yield only briefly touched 5% and mostly remained below 4.5%. More tellingly, since the Fed began cutting rates in late 2024, long-term yields have remained elevated. Even as the fed funds rate declined to around 3.75% by early 2026, the 30-year Treasury yield continued to trade above 4.75% on average—higher than during much of the period when policy rates were at their peak.

Fed Funds Rate Has Less Impact on Long-Term Rates

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

This divergence highlights an important reality: Policy rate cuts do not automatically translate into lower long-term borrowing costs.

Inflation expectations drive the long end of the curve. The primary driver of long-term Treasury yields is inflation expectations. The longer the maturity, the more investors focus on preserving real purchasing power over time. A 30-year bond is priced less on where overnight rates are today and more on where inflation is expected to average over decades.

This is why long-term yields often move less closely with near-term monetary policy. Even meaningful reductions in short-term rates may have little impact on long-term yields if inflation expectations remain firm. In this sense, monetary easing does not necessarily imply easier financial conditions across the entire yield curve.

As a result, while short-term rates are likely to fall further if monetary policy easing continues, long-term rates appear more likely to remain elevated. Medium-term rates may drift modestly lower, but without a dramatic reversion to pre-pandemic levels.

Fiscal fundamentals still matter. Another critical, and often underappreciated, factor shaping Treasury yields is fiscal policy. Treasury securities represent the borrowing cost of the U.S. government and, like any borrower, that cost reflects perceived creditworthiness, debt levels and future supply.

Focusing exclusively on central bank actions can obscure this reality. Persistent deficits and rising debt issuance influence the term premium investors demand, particularly at longer maturities. Even in a world of lower policy rates, sustained government borrowing could keep long-term yields elevated as investors require compensation for duration, inflation risk and oversupply.

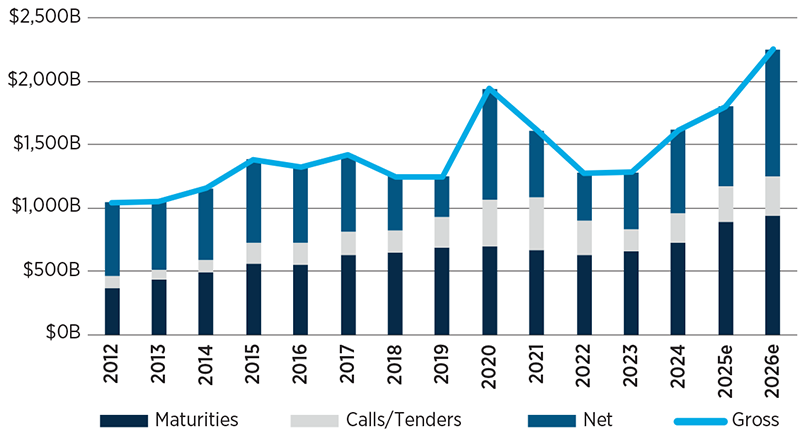

A market supply shock is emerging. Beyond policy considerations, market structure itself is becoming an important force in 2026. Rapid growth in artificial intelligence-related capital expenditures is driving a surge in investment-grade corporate debt issuance. Estimates from Wall Street suggest issuances could reach as high as $2.25 trillion.

Investment-Grade Debt Issuance

Source: Apollo Academy.

Source: Apollo Academy.

This raises a key question: Who will absorb this supply?

If investors fund new corporate bond purchases by reallocating away from Treasurys, Treasury yields face upward pressure. If the reallocation comes from mortgage-backed securities, mortgage spreads are likely to widen. Either outcome results in higher borrowing costs somewhere in the system.

Crucially, this dynamic operates largely independently of Fed policy. Even in an environment of easing monetary conditions, rising bond supply can push yields and credit spreads higher.

Looking ahead, interest rates are unlikely to move uniformly lower. With the Fed pausing rate cuts in January, short-term rates—which move in lockstep with the fed funds rate—should likewise remain near current levels. Renewed declines in short-term rates will most likely occur in the second quarter, when a change in Federal Reserve Board chairmanship could coincide with a resumption of monetary easing. Medium-term rates may ease modestly with volatility. Long-term rates, however, are likely to remain elevated, shaped more by inflation expectations, fiscal dynamics and bond supply than by the path of overnight policy rates set by the Fed.